Why you should ignore everyone and use Duolingo to start Mandarin

Duolingo gets a hard time on the internet. People love to bash it and those that use it a little each day. This is true for the most popular languages for English speakers on Duolingo (French and Spanish, which are also the most complete courses), but especially so for Chinese. On Duolingo you can learn Mandarin if you’re an English speaker, and Cantonese too if you already speak Mandarin; here I’m just going to focus on learning Mandarin.

For lots of people, Duolingo is an attractive option to get started without putting in a lot of time and money, but so many blog posts and reddit comments are dedicated to how much of a waste of time it is and how little you will learn for your time and effort. Some are mild rebukes, like this one, but a lot of off-hand comments online have a bit more disdain behind them. Why so much hate for Mandarin in particular? Perhaps because there are similar alternatives out there, like HelloChinese, or because it’s so markedly different to English that people quickly feel out of their depths with hard-to-understand grammar and characters.

I think it’s time the scales were pushed back the other way a little. Apps for language learning in general could use a little love. A lot of the hate is from people that have used it, complaining that Duolingo didn’t make them fluent, or from people that haven’t used it but that take umbrage with people trying to learn an extremely difficult language with just a few minutes a day. I should probably say before we go any further that I have no stakes in Duolingo. It’s also not my main or even preferred language learning tool, but I disagree with the notion that it is a bad idea for beginners to even consider it.

Dismantling the reasons against

So lets start with what some people say about Duolingo to turn others away. Here are the complaints I’ve seen the most often, and why they’re not really issues that should stop you using it.

It won’t make you fluent

Well, duh. No single app, book, podcast, language class, holiday, TV series or any other method will make you fluent. It’s something that’s so obvious that one would think it doesn’t need saying, and yet it’s the statement I see most often. Even if people ask on reddit or elsewhere about Duolingo, others are quick to add that it won’t make the poster fluent. I genuinely don’t think there are any individuals out there blindly plugging away at their Duo streak, expecting to become fluent by the time they get through all the lessons. And if there are, why deter them? They’re busy, determined (so determined that they didn’t even think much about how to become fluent), and presumably enjoying themselves enough to continue with it. I don’t think reminding everyone yet again that an app doesn’t magically bring about fluency is helping anyone.

The sentences are random

Sometimes. I see a lot of screenshots of seemingly random sentences in forums or youtube videos. I’ve used Duolingo for four languages and never come across anything completely random. The Duo team themselves claim this is intentional, to get you to remember through giving you sentences which stand out. The obvious reply to this that I have seen is that it is better to teach grammar through common native sentences than through unusual ones you won’t see in the wild. I see both sides of this. I will say though that the argument for using commonplace native sentences again seems to fall into the trap of assuming Duolingo is the sole source of your learning, whereas the Duo response seems to be more in line with the idea that the app teaches you grammar structures, and then you go seek native content elsewhere i.e. they want to give you stand-out sentences that you remember, but then you expose yourself to a lot of native content through immersion, even if they won’t admit this. This seems a lot more sensible to me than assuming Duolingo will be your native language immersion source.

You’re always translating

The argument here typically goes something like this: when using Duolingo, you are asked to convert from English to Chinese or vice versa. However, the goal of language learning should be thinkly directly in Chinese, without first turning to English and then mentally looking up a translation. Again, I think this comes from an assumption that Duolingo is your native language source for immersion and exposure to a lot of dialogues. It’s not. Besides this, basically all language learning involves translation at the early stages (including classroom and textbook learning), and making use of it affords the opportunity to use all the translation-based games using in the app to help drill basic vocabulary and grammar. I think translating is often a necessary but temporary feature of initial language learning and, like the fluency complaint, it’s something you could levy at basically any language learning method.

It doesn’t teach grammar

I don’t think this is true. It certainly doesn’t lead with long explanations of grammar, but this is no bad thing (see below). It does have a tips section for each lesson which gives you the essential grammar from the lesson. This used to be only available on the website (yes, there’s a website version) for Mandarin, but now you can use it in the app too. For the most part though, you are learning grammar implicitly through exposure to sentences, as you should do. Having instructive sentences pitched at your level and minimal grammar explanations to get you through complex topics is exactly what you want as a beginner. Leading with grammar would be, in my opinion, insane. And if you want to follow with more grammar, you can go to somewhere specifically focused on it, like the excellent Chinese grammar wiki.

I have found the grammar wiki to be immensely helpful because of its concise explanations. It is also written partly by John Pasden, who is the co-creator of the Mandarin Companion graded reader series. This makes it especially useful for getting up to speed on any grammar you think you might be missing to fully understand the graded readers they produce.

It won’t teach you characters

I suppose it doesn’t teach you stroke order or radicals, but it does actually do characters quite well. Stroke order is done so well by pleco that there’s no point trying to implement it within Duolingo, and radicals can be googled or learned through something like skritter (I think their initial 100 most common radicals list may even be free to use). Focussing on whole characters though, Duo is actually better than some other apps like HelloChinese, which focus on whole words but don’t drill you the characters which make the words. I find Duolingo to actually be useful for this when those characters are later recombined. It’s also a little suprising to realise you can recognise and read a character in a word but can’t read it when it appears by itself.

It’s too slow

Language learning doesn’t need to be a race. Why are you learning? Is there a deadline? If there is then I agree, you would likely do better to take an intensive course and then go straight to the country. But this isn’t the case for 99% of people, and if it is then it’s probably a company requirement that they will finance and support. For most of us, we learn a language for fun. So where’s the rush? If it’s fun and doable for you to go faster then go for it, but I suspect that if you think Duolingo is too slow for Chinese then you already have a headstart somehow (you know the writing system from Japanese/Cantonese, you learned years ago and are picking it up again), or you’re skimming through the basics too quickly without doing enough repetition to ensure you have a solid foundation. Even worse, you could be making the common mistake of getting so excited by early progress, and keen to make an even bigger impact, that you double-down on your language learning efforts and take on a tonne more resources and daily tasks, until eventually you burnout and stop learning the language altogether. I think this massive conflagration of learning that then dies out is how many passionate learners fail to become fluent in Mandarin.

Duolingo should by no means be your only method. This is common sense. Starting Mandarin involved exposure to language through podcasts and netflix for me, and some more formal learning with HSK textbooks. But don’t take them all on at once. Pick a simple routine and stick to it every day. Again, I think this is obvious stuff, but sometimes it bears repeating.

The case for Duolingo

Okay, so we have seen the main reasons people give for not using Duolingo. I hope it’s clear so far that none of these are good enough reasons to avoid using it. But that’s not enough to recommend something. We also need to know what the positives are. Here are the main benefits I see from using it.

Gamification is immensely helpful in forming a habit

In my opinion this is the single biggest reason to use Duolingo. Gamification is an effort to include concepts from gaming, like winning points and levelling up, to other tasks in order to improve the experience or make it more likely the user will come back. As most of us know, forming habits is hard, and it often takes special effort and tactics like tagging our habit onto an existing one to help it stick. I have no shame (and nor should anyone!) in admitting I need this for Chinese. I love the language, culture and have Big Dreams of fluidly writing Mandarin, but this passion just isn’t enough to get me to come back every day and keep practising. We need both the Big Why to motivate us in the long term, and practical routines for habit forming and daily practice in the short term. The latter is where gamification comes in. With duolingo, you get a lot of this, and more so than with many other apps. This comes in many forms, including notifications which entice you to learn new words and remind you of your streak, visual encouragements when you complete a task or extend a streak even further, a combination of auditory and visual response when you select the correct answer, and so on.

You might think that you can achieve all this with timetables, alarms, rewards for yourself - essentially finding other ways to get a dopamine fix. If so, I think you’re undestimating the amount that goes in to gamification. But also, why would I give up time to plan an elaborate custom routine, when a company has already paid engineers to mine user data and maximise continued use of their app, and then made that app available to use for free (if you ignore time watching ads). Someone has already optimised langauge habit forming for me, and (effectively) for free, I can make daily language learning a habit just by using their app. Why wouldn’t I do that? For me this is the biggest reason to use duolingo in the beginning.

It helps drill characters within words

This is really the flipside of the response earlier, so I won’t dwell on it. The other most popular app in this area, HelloChinese focuses on words and sentences. This is great, but having the invidual characters drilled too is helpful for recognising them in new contexts. I don’t view this as a strong for argument though, as you can use a specific character app like skritter to do this.

It doesn’t teach too much grammar

Funnily, I see the line that you don’t learn much grammar in Duolingo as a fairly frequent criticism, but I see this as a big plus. As I mentioned earlier, too much grammar up-front is pointless if you have no experience of the language to attach it to. A small amount of explanation is good for difficult sentence structures where it is hard to understand from context alone, but in my view that should be all you get from a course or app. If you want to follow it up in more detail, as I sometimes do, you can do that yourself elsewhere. But it shouldn’t be spoonfed to you in advance of being exposed to the actual language.

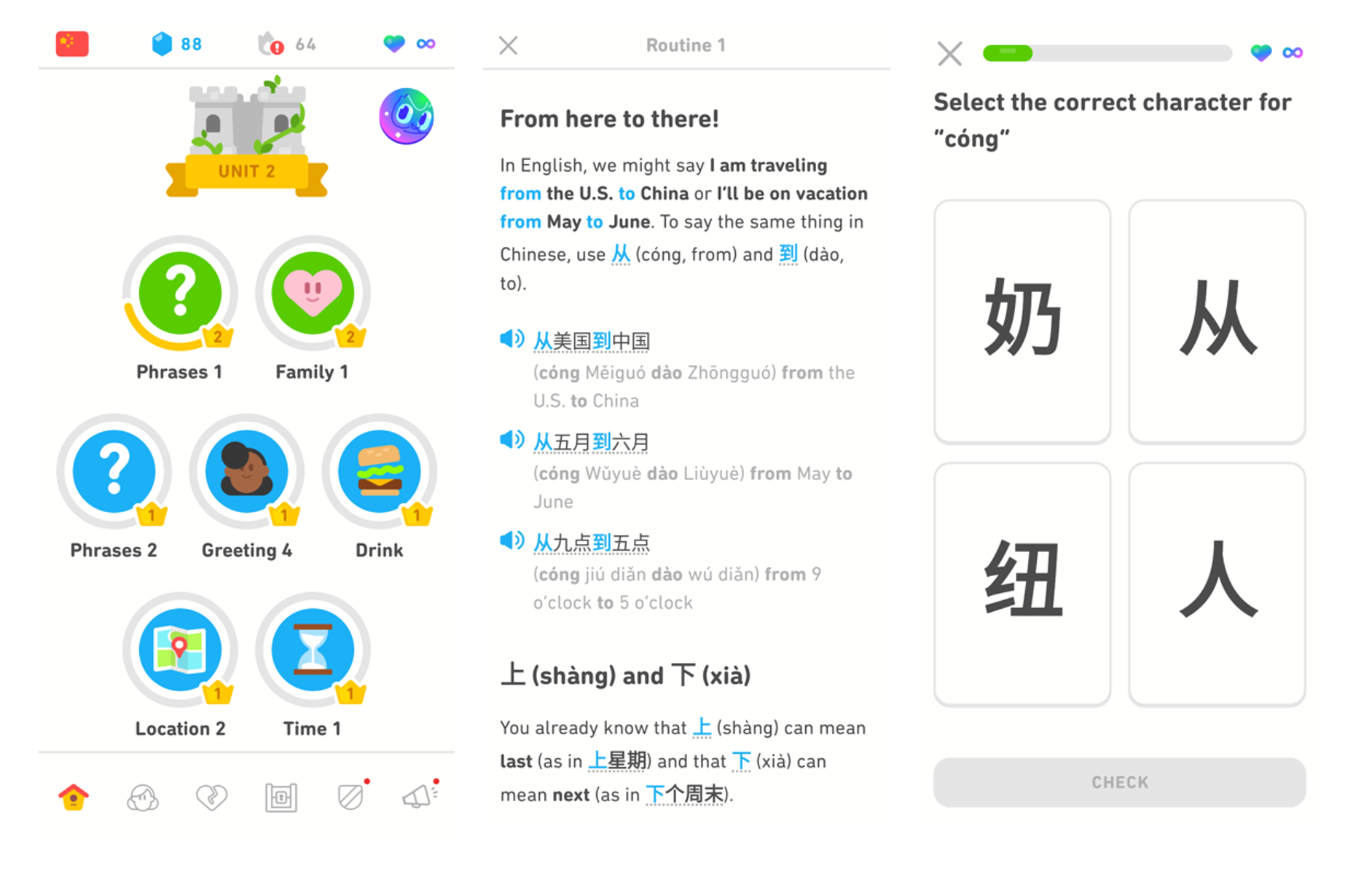

The Duolingo pathway, tips page and a lesson. The tips pages are sometimes just very short sections covering basic pinyin at the start, but they can quickly grow to be short grammar lessons that help you understand a unit.

It keeps learning fun

Another big plus is that doing a short Duolingo lesson is enjoyable. When you know the very basics really well and are constantly pushing to learn new things then you can be making a lot of progress without really feeling it. Even reading over or listening to easier material can not give you a confidence boost sometimes because a different accent or sentence structure throws you off, or you experience the surprisingly commonplace scenario where you know all the characters in the sentence but still don’t understand its meaning. However, I can go back over a very early lesson from Duolingo and it reminds me how much I know, whilst also giving me the immediate feedback of a game to make me feel good about it. I can be sure I know it because it’s something I went over previously. I think this kind of quick confidence boost is an underappreciated side-benefit of using apps to help learn a language, and the impact of it is really important for complex languages (coming from an English background) where it is easy to feel out of your depth and like you haven’t mastered anything. Ultimately, I want to be having as much fun as possible and simple game-like lesssons can help remind me of that. I often start my Mandarin practice off this way as it gives me the mental boost to carry on with other materials for the next few hours which are more challenging, like textbooks and anki.

The takeaway

I think the basic message here is simple. The hate for Duolingo for learning any language, especially Mandarin, is excessive. Some people only have a few minutes each day to spare, or just want to try out languages before commiting more time and energy. Duolingo is great for this. Some people want to get into a language more seriously and work towards fluency and beyond. Duolingo can still help with things like forming a habit and getting some of the basics down. Will it make you fluent? No. But you didn’t think it would. No-one does. Anyone that has ever spoken a language is intuitively aware of the fact that they won’t reach fluency from an app or a single method. This is true for Duolingo, Pimsleur, and anything else you come across. If you’re going to use it then you need to supplement it with writing practice, native audio, speaking practice with native speakers etc.

This post could quite easily have just been a defence of language learning apps, or a defence of people using any method they like as long as it helps form the habit of practice and makes the learning journey enjoyable for them. In general, I think there is too much time spent trying to optimise the perfect way to learn a language, and not enough time just learning it. To me it seems a bit like telling your child to be quiet so you can focus on reading your parenting book. The important thing is showing up everyday, not doing it perfectly.

In the end, I think so many of the complaints about Duolingo are moot because almost everybody knows the common criticisms, like that it won’t make you fluent, and as I have gone over, these alone should not be sufficient to deter you. So, should you use Duolingo for Mandarin? Yes. Just also use other stuff. But you knew that already, because everyone does.